In April, Coca-Cola proudly launched a new ad campaign it called “Classic,” celebrating famous authors and the sugary drink’s omnipresence in culture by highlighting classic literary works that mention the brand. The firm that produced the ad campaign said it used AI to scan books for mentions of Coca-Cola, and then put viewers in the point of view of the author, typing that portion of the text on a typewriter. The only issue is that the AI got some very basic facts about the authors and their work entirely wrong.

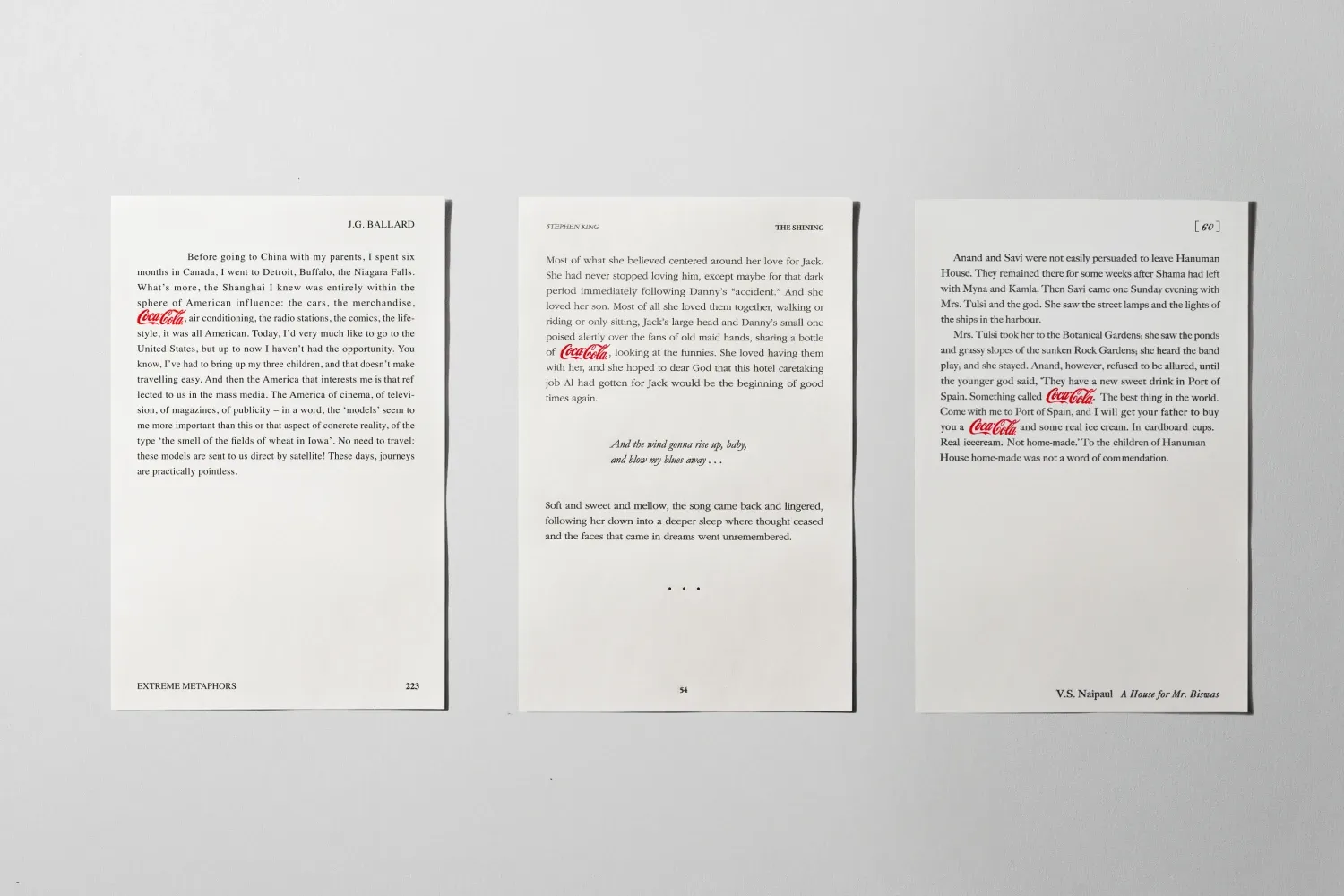

One of the ads highlights the work of J.G. Ballard, the British author perhaps best known for his controversial masterpiece, Crash, and David Cronenberg’s film adaptation of the novel. In the ad, we get a first person perspective of someone typing a sentence from “Extreme Metaphors by J.G Ballard,” which according to the ad was written in 1967. When the sentence gets to the mention of “Coca-Cola,” the typeface changes from the generic typewriter font to Coca-Cola’s iconic red logo.

“Before going to China with my parents, I spent six months in Canada, I went to Detroit, Buffalo, the Niagara falls. What’s more, the Shangai [sic] I knew was entirely within the sphere of American influence,” says the text that appears on the page as the typewriter clack. “The cars, the merchandise, Coca-Cola, air conditioning, the radio stations, the comics, the lifestyle, it was all American.”

When the typewriter types Coca-Cola’s logo we can hear the pop and fizz of a carbonated bottle opening.

J.G. Ballard never wrote a book called “Extreme Metaphors,” and he never wrote the words that appear on the page in the ad. In reality, “Extreme Metaphors,” actual full title: Extreme Metaphors: Selected Interviews with J. G. Ballard 1967-2008, is a book edited by Dan O’Hara and Simon Sellars which collects interviews with J.G. Ballard that was published in 2012, three years after the author’s death. The words in the ad were not written, but spoken by Ballard in an interview with the French Magazine Littéraire in 1985. Ballard spoke in English, the magazine translated his words to French, and O’Hara told me he translated that printed French back to English.

“The sequence of words being typed out by the imagined J. G. Ballard in the ad was never written by him, only spoken, and the only person ever to type that exact sequence out in English is me,” O’Hara told me. “What most outraged my eye was the word ‘Shangai’ being typed. Ballard would never have misspelled the name of the city in which he was born. Seeing the ad triggered an academic neurosis: had I? I checked my copy of Extreme Metaphors and, thank god, no: it’s printed as Shanghai in the original text.”

“For the creation of ‘Classic’ AI was leveraged in the initial research phase to identify books with brand mentions,” a spokesperson for VML, a WPP agency behind the ad, told me in an email. “After that, we conducted a manual scan of credible sources to ensure accuracy and due diligence and secured permission from all involved publishers, authors and estates.”

WPP’s Open, “an AI-powered Production Studio,” collaborated on the ad. Coca-Cola also recently got some bad press about a different AI-generated ad, but this one was produced by a different agency.

VML did not respond to specific questions about inaccuracies in the ad. Coca-Cola and the J.G. Ballard estate did not respond to a request for comment. At the time of writing, the ad is still up on YouTube, errors and all.

A source who was familiar with the details of the deal who asked to remain anonymous told me that the Ballard estate was not aware the ad used AI in any way.

“If you read the text in the ad, you’re not reading his prose: you’re reading mine, translating his recorded words from French,” O’Hara said. “I’ve done my best to render his meaning, but that’s all I’ve managed to do. My prose is a pretty poor substitute for the real thing, and I feel anyone seeing the ad and thinking there’s nothing special about the writing is both right, and misled to think it’s Ballard’s own writing.”

“I think I had to translate five of the interviews in the book into English, including the one used in the ad, and getting the tone and feel of a particular speaker right is an art and an endeavour in itself,” O’Hara added. “All of that is made evident by and in the book itself, and the relation between the authors and Ballard is clear. Coca-Cola’s ad erases all of that. But on the other hand, I’m not going to argue with Coca-Cola describing Extreme Metaphors as a literary classic!”

Another clue that the people who made this ad do not really understand or care about Ballard’s work is that they chose to highlight it in the first place. His most famous novel, Crash, is about people who are turned on and have sex in terrible car crashes. Not exactly brand friendly. It is also, as Ballard himself said, about how technology can exploit us all, a very common complaint against generative AI.

“I would still like to think that Crash is the first pornographic novel based on technology,” Ballard wrote in his 1995 introduction to the novel. “In a sense, pornography is the most political form of fiction, dealing with how we use and exploit each other, in the most urgent and ruthless way. Needless to say, the ultimate role of Crash is cautionary, a warning against that brutal, erotic and overlit realm that beckons more and more persuasively to us from the margins of the technological landscape.”