On Monday, a publicly-sourced archive of more than 10,000 national park signs and monument placards went public as part of a massive volunteer project to save historical and educational placards from around the country that risk removal by the Trump administration.

Visitors to national parks and other public monuments at more than 300 sites across the U.S. took photos of signs and submitted them to the archive to be saved in case they’re ever removed in the wake of the Trump administration’s rewriting of park history. The full archive is available here, with submissions from July to the end of September.

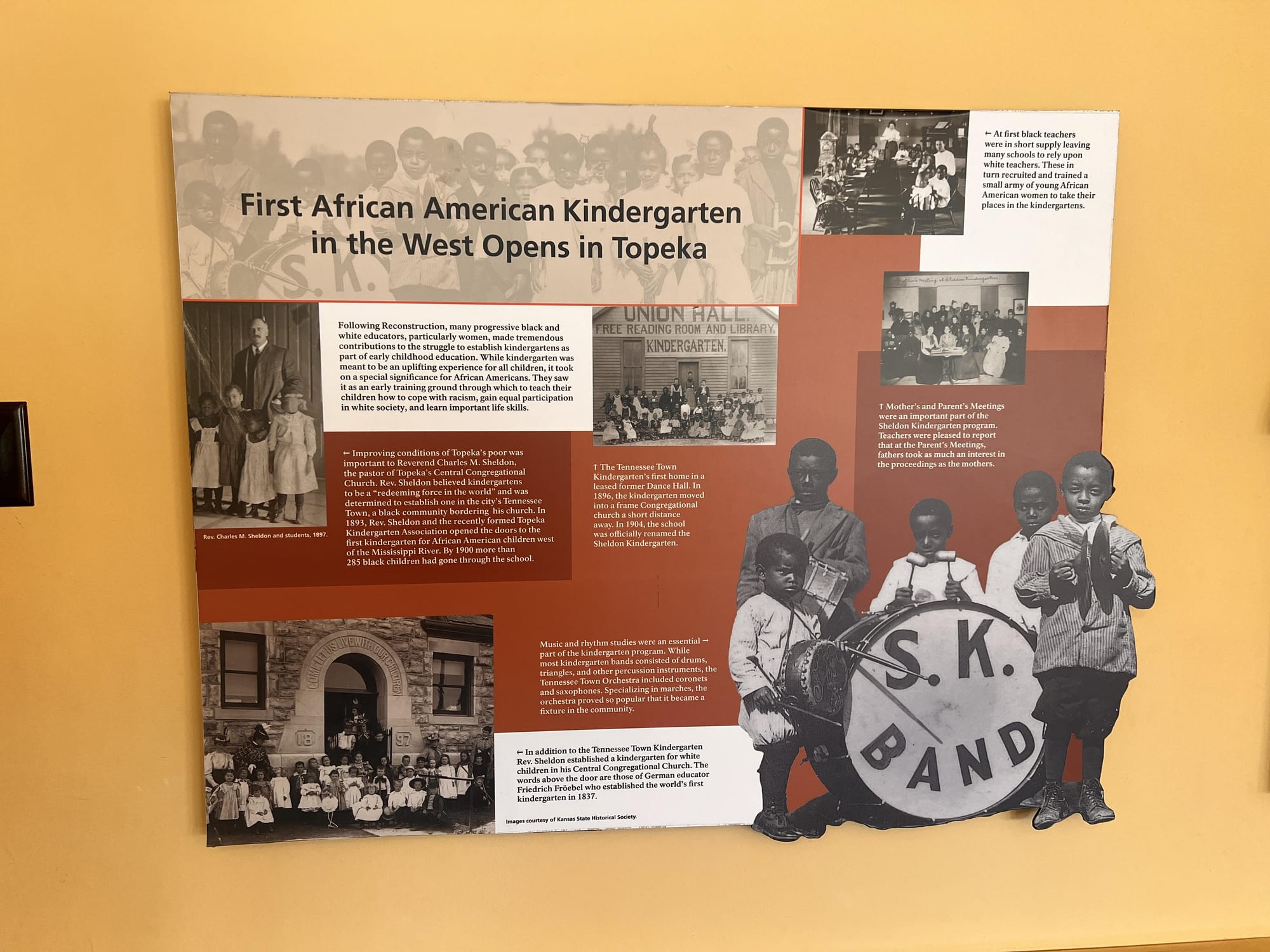

The signs people have captured include historical photos from Alcatraz, stories from the African American Civil War Memorial, photos and accounts from the Brown v. Board of Education National History Park, and hundreds more sites.

Launched in July by volunteer preservationists from Safeguarding Research & Culture and the Data Rescue Project, in collaboration with librarians at the University of Minnesota, Save Our Signs started in response to President Donald Trump’s executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” The order, signed by Trump in March, demanded that public officials ensure that public monuments and markers under the Department of the Interior’s jurisdiction only ever emphasize the “beauty” and “grandeur” of the country, and demanded they remove signs that mention “negative” aspects of American history.

The order gave a deadline of September 17, and by September 20, some signs were already going missing, including signs at Acadia National Park in Maine that referenced climate change, and another at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in New York City that referenced historical events like slavery, Japanese camps and conflicts with Native Americans, according to the Washington Post.

Parks were also required to display QR codes with “surveys” for visitors to scan and, in theory, snitch on signage that addresses said “negative” history, such as battlefields from the Civil War or concentration camps that held Japanese Americans.

The order and destruction of such signage represented another step in the Trump administration’s efforts to whitewash, alter or completely delete important public information about history, research, and science. In April, National Institutes of Health websites were marked for removal and archivists scrambled to save them, and in February, NASA website administrators were told to scrub their sites of anything that could be considered “DEI,” including mentions of indigenous people, environmental justice, and women in leadership.

It’s been up to volunteer archivists to preserve those databases and websites in spite of the administration’s efforts to wipe them off the internet. Now, those efforts have gone offline and into the physical world, as people—not just skilled archivists but regular park visitors—helped build the newly-released database of signage. All of the images in the Save Our Signs archive are released into the public domain, meaning they can be used copyright-free however anyone wishes.

Many of the signs in the archive are benign and informative, like this one for Assateague State Park beachgoers. Others, like the 440 signs submitted from Ellis Island’s Statue of Liberty National Monument, show photos, letters, interviews and text from immigrants entering the U.S. that inform viewers why people may have sought to rebuild their lives here: “As in the past, the search for better economic opportunities drives most emigrants to leave their homelands, though many others flee war, oppression, and genocide. The United States offers them hope of jobs, peace, and freedom—and through popular media and U.S. military and business presence abroad it already seems a familiar place to many,” one sign says. “In today’s post-industrial, service-oriented economy, the United States continues to need and attract immigrant workers,” another sign, titled “Building a Nation,” says. “Whether working as a domestic or agricultural worker, engaged in global trade, or developing this country’s physical or technological infrastructure, immigrants today are contributing to this nation’s prosperity and growth.”

Visitors submitted dozens of signs with text from the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Washington, D.C., including several quotes from Douglass: “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future,” one sign captured in the archive, quoting the abolitionist statesman’s “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July” address, says. “To all inspiring motives, to noble deeds which can be gained from the past, we are welcome. But now is the time, the important time. Your fathers have lived, died, and you must do your work.”

“I’m so excited to share this collaborative photo collection with the public. As librarians, our goal is to preserve the knowledge and stories told in these signs. We want to put the signs back in the people’s hands,” Jenny McBurney, Government Publications Librarian at the University of Minnesota and one of the co-founders of the Save Our Signs project, said in a press release. “We are so grateful for all the people who have contributed their time and energy to this project. The outpouring of support has been so heartening. We hope the launch of this archive is a way for people to see all their work come together.”

People can still submit signs, and the project organizers are encouraging more submissions; another batch with more recent submissions will be released in the future, the Save Our Signs organizers said.