Welcome back to the Abstract, and Happy New Year! Here are the studies this week that stoked the flames, cooled off, then went feral and rogue.

First, the ashy remains of a cremation pyre reveal a rare glimpse of an ancient ritual. Then: Uranus is chilling, ham on the lam, and a Saturn without a Sun.

As always, for more of my work, check out my book First Contact: The Story of Our Obsession with Aliens or subscribe to my personal newsletter the BeX Files.

An ancient cremation comes to light

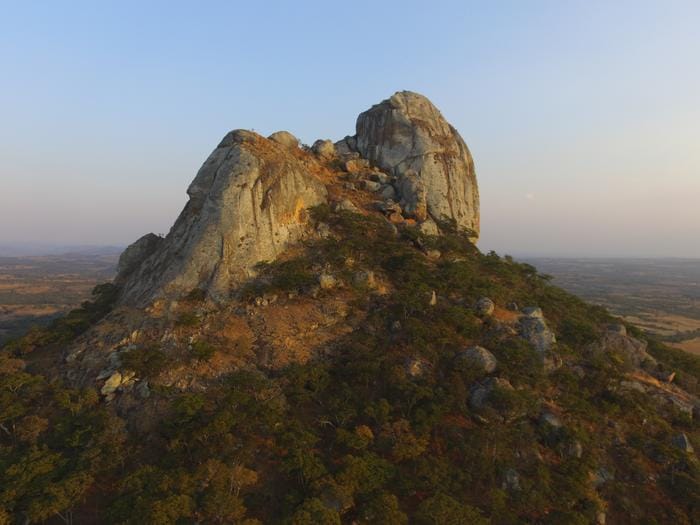

Some 9,500 years ago, a community of hunter-gatherers assembled to cremate a small woman in a ceremonial pyre at a rock shelter near Mount Hora in Malawi.

Millennia passed. Many things happened. And now, at the dawn of the year 2026, scientists report the unearthing of the ashy remains of this ritual at a site, called HOR-1, which is “the oldest known cremation in Africa” and “one of the oldest in the world,” according to their study.

“Archaeological evidence for cremation amongst African hunter-gatherers is extremely rare, with no reported cases south of the Sahara,” said researchers led by Jessica I. Cerezo-Román of the University of Oklahoma. “Open pyre cremations such as that at HOR-1 demand substantial social and labor-intensive investment on behalf of the deceased. Thus, cremation is rarely practiced amongst small-scale hunter-gatherer societies.”

Indeed, before reading this study, I did not fully appreciate the work that goes into cremating a corpse from scratch. For a body to be properly reduced to ash in this prehistoric era, a community had to collect tinder, build the pyre, ignite it, and then keep the flames stoked at high temperatures for around seven to nine hours by continually adding more fuel.

The process would have been long and arduous, suggesting that it held a significant meaning to these prehistoric attendees. This ancient rock shelter was clearly used for mortuary practices over millennia, which “reflect a deep-rooted tradition of repeatedly using and revisiting the site, intricately linked to memory-making,” the researchers said.

The oldest known pyre, located in Alaska, dates back 11,500 years and contains the created remains of a 3-year-old child. But HOR-1 is the oldest example of adult cremated remains found in a pyre. We will likely never know the identity of this woman, or why her death inspired such a carefully coordinated ritual. But it seems safe to assume that the cremation was a significant event for the community that expended so much forethought and labor to perform it.

“While this cremation is highly unusual in the African archaeological record, it contributes to growing evidence of complex social worldviews among tropical African hunter-gatherers,” they added. “These practices emphasize complex mortuary and ritual activities with origins predating the advent of food production.”

In other news…

The inexplicable Uranian chillout

Uranus is so cool. I mean this in the flattering vernacular sense—Uranus is genuinely nifty—but it’s also literally true. Not only is this ice giant the coldest planet in the solar system, its upper atmosphere (the thermosphere) has been getting steadily cooler for the past 40 years—and nobody really knows why.

Scientists now think they have ruled out a hypothesis that linked this long-term thermospheric cooling to a weakening of the solar wind, which is a stream of energetic radiation and particles emitted by the Sun. A new analysis suggests that this weakening effect has reversed over the past 15 years, hinting that it is not the cause of the cooldown.

“We determine that the solar wind kinetic power at Uranus has increased by ∼28% since the start of solar cycle 24 (at the end of 2008),” said researchers led by Jamie M. Jasinski at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“If the solar wind is a driver of Uranus’ thermospheric temperature, then one would have expected a gradual increase in the temperature since then. However, the temperature has continued to consistently decline over the same time period. Therefore…we argue that the solar wind kinetic power is unlikely to be the primary driver of thermospheric temperature at Uranus.”

As for the real cause, the truth is still out there. May this mystery inspire a new generation of Uranian scientists.

When pigs sail…

Now, for the incredible adventures of ancient seafaring pigs. Today, many domestic and feral pig lineages are scattered across the Pacific islands of Wallacea, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia; their ancestors were schlepped over the oceans by early mariners in several migratory waves.

To learn more about how these boats brought home the bacon, scientists sequenced 117 modern, historical, and ancient pig genomes spanning nearly 3,000 years. The results revealed that pigs from Indonesia to Hawaii are mostly descended from a group of domestic pigs that voyaged with Austronesian-speaking groups from Southeast China and Taiwan about 4,000 years ago.

“Transporting these animals between islands resulted in a distinctive evolutionary history characterized by serial founder effects, gene flow from divergent lineages, and likely selection for specific traits that facilitated the establishment of feral populations,” said researchers led by David W.G. Stanton of Queen Mary University of London and Cardiff University.

In other words, some of the most significant Pacific voyages also doubled as piggyback rides.

A glimpse of a sunless Saturn

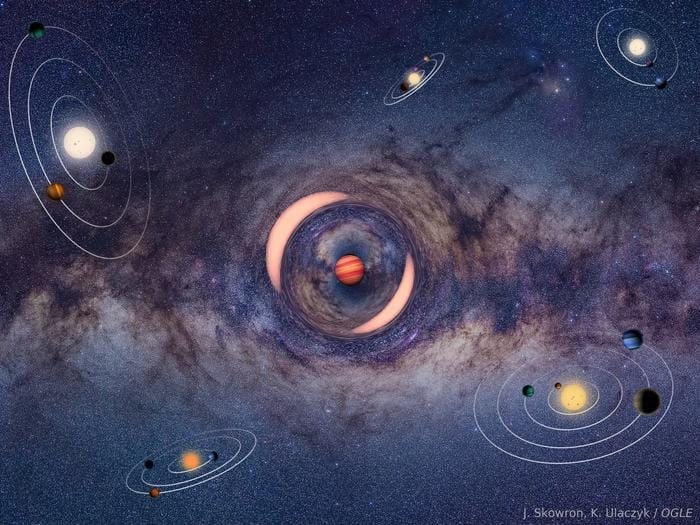

I don’t mean to cause alarm, but there’s a rogue Saturn on the loose in the galaxy.

Astronomers spotted this world drifting through interstellar space, untethered to any star, with a trippy technique known as microlensing. When a distant planet passes in front of a star from our perspective on Earth, its gravitational field warps the background starlight, creating a distinctive light signature that exposes its presence (for more on microlensing, here’s a short feature I wrote).

Now, a team has captured a microlensing event with telescopes located on both the ground and in space, a combination that allowed them to calculate the foreground planet’s mass (Saturn-ish) and its distance from Earth, which is about 10,000 light years. Based on its mass and its very quick pace through space, this gas giant was probably born around a star, but was flung out of its home system by gravitational interactions between neighboring stars or planets.

“We conclude that violent dynamical processes shape the demographics of planetary-mass objects, both those that remain bound to their host stars and those that are expelled to become free floating,” said researchers led by Subo Dong of Peking University.

It’s a reminder that as bad as things seem sometimes here on Earth, at least our planet hasn’t been violently ejected from the solar system to drift endlessly in the dark. Small wins!

Thanks for reading! See you next week.